What Is Geopolitics?

“geo” = geography

Aristotle founded classical geopolitics by deriving the political systems of Greek city-states from their climatic and geographic features.

Swedish geographer Rudolf Kjellén, who coined the term “geopolitics” in 1916, and German geographer Friedrich Ratzel, who wrote about how states derive their power as nations from the territory they occupy in 1897, serve as the most popular starting points for classical geopolitics.

Geopolitics Definition: The struggle over the control of geographical entities with an international and global dimension and the use of such geographical entities for political advantage (Flint, 2021).

We can use geopolitics as a framework to comprehend the complex environment we live in. In order to “get what you want in the world” or in global politics, one must think and act locally. What does that mean, though? Geopolitics explains how nations, corporations, terrorist organizations, etc., attempt to achieve their political objectives by influencing the world’s geographical features. These are what we refer to as geographical entities. The locations, regions, territories, scales, and networks that make up the globe are referred to as geographic entities.

Dodds (2007) said three qualities are involved in geopolitics.

It is first concerned with issues of power to influence and dominance over territory.

In order to make sense of global affairs, it also employs geographic frames.

Third, geopolitics has a focus on the future.

Geopolitics is the study of how geography affects politics and international relations. Under geopolitics, analysts study actors and how the interact with one another.

It offers insights into the likely behavior of states because their interests are fundamentally unchanging. States need to secure resources, protect their territory, including borderlands, and manage their populations.

Two fundamental ways of understanding the term geopolitics are offered: classical geopolitics, which focuses on the interrelationship between the territorial interests and power of the state and geographical environments, and critical geopolitics, which tends to focus more on the role of discourse and ideology.

The presumptions of classical geopolitics regarding the constraining influence of geography were rather rigid. Many classical geopolitical studies began with the fundamental premise that geography is unchangeable and unavoidable. Therefore, a country will always be able to impose its will on other countries and have a permanent political advantage if it occupies certain strategic territories or has access to key chokepoints in international waters.

Halford Mackinder (1919) argues, “Who rules East Europe commands the [Eurasian] Heartland; who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island; who rules the World-Island commands the world.”

If that were the truth, the Soviet Union, which ruled Eastern Europe and the heartland of Eurasia, would have been the winner of the Cold War.

Modern geopolitics views geography as a set of opportunities and limitations that affect the decision-makers range of options rather than as an unchangeable destiny.

This geographical factor, together with the political options chosen, can lead to very different outcomes from region to region.

For instance, Cohen (1991) distinguished between “gateways” and “shatter belts.”

Gateways are regions where various societies and nations foster international cooperation and economic growth. The European Union and the nations taking part in China’s Belt and Road Initiative are two well-known examples of gateways.

Shatter belts are regions where there are frequent interregional conflicts and competition among foreign powers for sway, as we see in the Middle East.

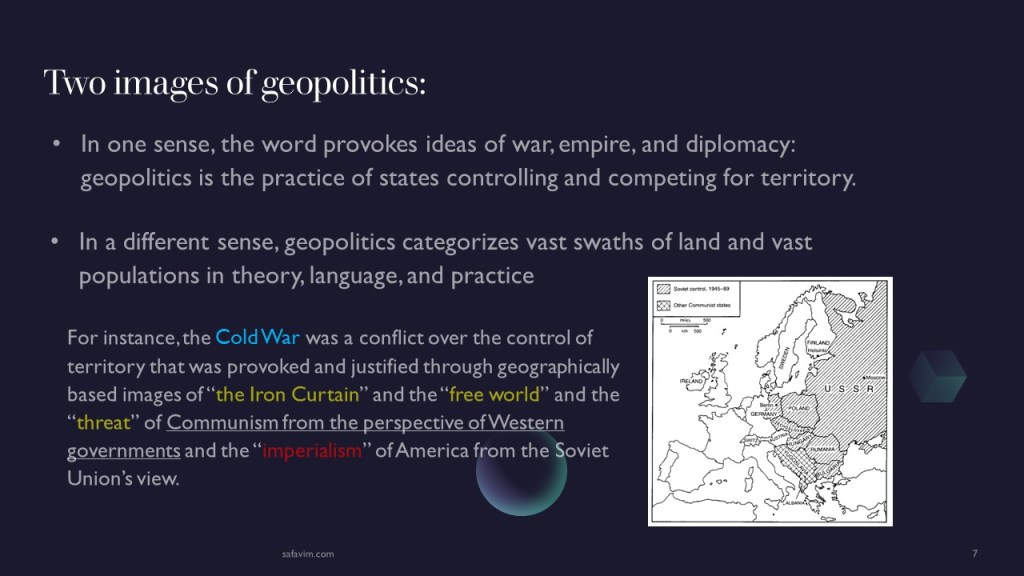

Two images of geopolitics:

- In one sense, the word provokes ideas of war, empire, and diplomacy: geopolitics is the practice of states controlling and competing for territory.

- In a different sense, geopolitics categorizes vast swaths of land and vast populations in theory, language, and practice.

For instance, the Cold War, was a conflict over the control of territory that was provoked and justified through geographically based images of “the Iron Curtain” and the “free world” and the “threat” of Communism from the perspective of Western governments and the “imperialism” of America from the Soviet Union’s view (Figure).

The three pillars of the contemporary geopolitical approach are described as follows by Scholvin (2016):

- Geographical factors shouldn’t be viewed as unchangeable destinies. They offer both opportunities and restrictions, but these restrictions and opportunities are dynamic.

- Geographical factors have a significant impact on long-term trends and general patterns, but non-geographical factors must be taken into account in order to comprehend specific developments in international affairs.

- It is useful for geopolitical scientists to focus on the role of geography in these causal mechanisms.

Bergesen and Suter (2018) argued that geopolitics follows long-term cycles in which periods of globalization and the removal of borders and geographical barriers alternate with periods of rising nationalism and the erection of (new) borders.

Geopolitical Actors:

State actors: National governments, political organizations, or other country leaders who have influence over the resources and security of their nation. For instance, the Malaysian Parliament, the British Prime Minister, and the President of South Africa.

Non-state actors: Organizations that take part in international issues on a political, economic, or financial level but do not directly manage the security or resources of their own country. NGOs, large corporations, charities, and even important people like corporate executives and cultural celebrities are a few examples.

Geopolitical risk

The risk posed by tensions or acts between players that have an impact on the regular and peaceful course of international relations is known as geopolitical risk. A change in policy, a natural disaster, a terrorist attack, a theft, or a war might all result in geopolitical risk.

Globalization

Globalization is the interaction and integration of individuals, organizations, and governments on a global scale. It has caused the transnational spread of goods, information, employment, and culture.

Globalization results from economic and financial cooperation and are predominantly driven by non-state organizations, including firms, people, and organizations.

Characteristics of globalization

Economic and financial cooperation, including active trading in products and services, capital flows, currency exchange, and cultural and information sharing, are characteristics of globalization.

The promotion of a country’s own economic interests at the expense of or in opposition to those of other nations is known as anti-globalization or nationalism. Limited economic and financial cooperation is a nationalistic trait.

Motivations for Globalization

- Improved profits: Increasing sales can boost profitability. Businesses can access new customers through globalization, which boosts sales of their products and services.

Cutting costs is another strategy to increase profitability. Companies can take advantage of reduced-tax operating environments, cheaper labor expenses, and other supply chain efficiency improvements because of globalization. These are all cost-cutting actions.

- Market and resource accessibility: Businesses require dependable access to resources like labor or raw materials. Companies may go global to increase access if these resources are not easily accessible or reasonably priced in the country where they are based.

Some investors might look for opportunities in international markets. There are two significant types of flows in this situation. Short-term investments in foreign stocks or bonds are known as portfolio investment flows. Alternatively, foreign direct investments (FDIs) are long-term investments in a foreign nation’s ability to produce. Intrinsic gain: An activity that has an unrelated benefit beyond profit is said to produce an intrinsic gain. The personal development or education that people can acquire through expanding their horizons, going to new places, or acquiring new concepts is an illustration of intrinsic gain.

Globalization’s costs and Consequences of Rollback

- Unequal accrual of economic and financial gains: Globalization tends to boost overall economic activity, but this does not guarantee that everyone will benefit. For instance, when a business moves a factory to another nation, it increases employment there while decreasing it in the original nation.

- Lower ESG standards: Businesses that operate in nations with lower costs frequently follow the local standards of such nations. Globalization can result in a drain on human, administrative, and environmental resources if the ESG requirements in one nation are lower than those in another and businesses adopt the lower standards.

- Political consequences: The two costs of globalization previously mentioned can result in a third cost of globalization or the political consequences of global expansion. While some nations might profit from higher labor force utilization, others would experience job losses as businesses move. Thus, income and wealth inequality, as well as disparities in opportunity within and between countries, could all be made worse by globalization.

- Interdependence: As a result of globalization, businesses may start to rely on the resources of other nations for their supply chains. Companies may not be able to make the goods themselves if the supply chain is disrupted, as was the case with the COVID-19 epidemic.

Reference

Bergesen, A., and C. Suter. 2018. “The Return of Geopolitics in the Early 21st Century: The Globalization/Geopolitics Cycles.” In The Return of Geopolitics, edited by A. Bergesen and C. Suter, 1–8. Munster, Germany: Lit Verlag.

Cohen, S. 1991. “Geopolitical Change in the Post-Cold War Era.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 81 (4): 551–80.

Dodds, K. (2007). Geopolitics: A very short introduction. OUP Oxford.

Flint, C. (2021). Introduction to geopolitics. Routledge.

Scholvin, S., and M. Wigell. 2018. “Power Politics by Economic Means: Geoeconomics as an Analytical Approach and Foreign Policy Practice.” Comparative Strategy 37 (1): 73–84.

#Globalization #Economics #Finance #Geopolitics #Teaching #Research

Leave a comment